Gradual Typing Across the Spectrum

Instead of being Pythonistas, Rubyists, or Racketeers we have to be scientists. — Matthias Felleisen

Yesterday we hosted a PI meeting for the Gradual Typing Across the Spectrum NSF grant, gathering researchers from a number of institutions who work on gradual typing (the meeting program can be found here). In case you aren’t familiar with gradual typing, the idea is to augment dynamically typed languages (think Python or Ruby) with static type annotations (as documentation, for debugging, or for tool support) that are guaranteed to be sound.

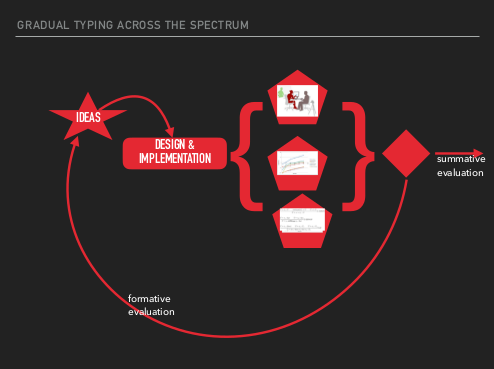

Gradual typing is these days a fairly popular area, but the research can seem fragmentary because of the need to support idiosyncratic language features. One of the points of the meeting was to encourage the cross-pollination of the key scientific ideas of gradual typing—the ideas that cross language and platform barriers.

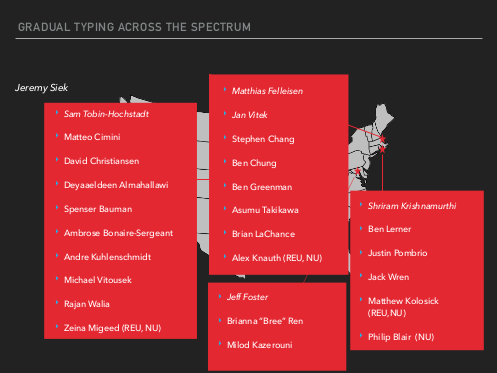

There were a good number of both institutions and programming languages represented at the meeting, with researchers from all of Brown University, Indiana University, Northeastern University, and the University of Maryland. The languages that we work on cover a broad subset of the dynamically-typed languages: Clojure, JavaScript, R, Racket, Ruby, Pyret, and Python.

The specific research artifacts that were represented include Reticulated Python, RDL (contracts for Ruby), StrongScript, Typed Clojure, and Typed Racket.

In this blog post, I’ll summarize some of the key research themes that were brought up at the meeting. Since I can’t go into too much detail about every topic, I will link to the relevant research papers and other resources.

At a high level, the talks covered four major facets of gradual typing: expressiveness, performance, usability, and implementation techniques.

Expressiveness

By expressiveness, I mean what kinds of language features a gradual type system supports and the richness of the reasoning that the type system provides. Since gradual typing is about augmenting existing dynamically-typed languages, a gradual type system should support the language features that programmers actually use.

This is why recent implementations of gradual typing have focused on enabling object-oriented programming, since objects are widely used in nearly all dynamically-typed languages in use today. Unfortunately, since different languages have wildly different object systems, it’s hard to compare research on gradual OO languages. Ben Chung is working to address this by coming up with a formal model that tries to unify various accounts of objects in order to better explain the design tradeoffs. His goal is to cover the core ideas in Reticulated Python, StrongScript, and Typed Racket.

Of course, dynamically-typed languages have a lot more than OO features. Along these lines, I gave a talk on how at NU we’re working to extend Typed Racket to cover everything from objects (my thesis topic), first-class modules (Dan Feltey’s MS project), and higher-order contracts (Brian LaChance’s MS project).

On the other side, as programs get more complex, programmers may wish to write richer type specifications that provide even more guarantees. This makes gradual typing a wide spectrum that goes from completely untyped, fully typed, and then beyond to dependently typed. Andrew Kent and David Christiansen both presented work that takes gradual typing beyond ordinary typed reasoning with dependent types.

Andrew presented an extension of Typed Racket that adds type refinements that can check rich properties (like vector bounds) that are found in real Racket code (see his RacketCon talk and recent PLDI paper). David Christiansen followed with a talk about adding dependent type theory to Typed Racket, which would allow correct-by-construction programming using a Nuprl-like proof system (he had a very cool GUI proof assistant demo in his slides!).

Performance

One of the key practical concerns about gradual typing is its performance overhead. It’s a concern because in order to ensure type safety, a gradually-typed language implementation needs to install dynamic checks between the typed and untyped parts of a program. This catches any inconsistencies between the typed interfaces and how the untyped code may call into them.

Ben Greenman gave an upbeat talk that set the stage for this topic, pointing out some key lessons that we’ve learned about performance from building Typed Racket. The main idea he presented (also the topic of our POPL 2016 paper) is that to evaluate a gradual type system, you want to explore different ways of adding types to a program and see how much it costs. This evaluation effort started with Typed Racket, but he and Zeina Migeed are working on expanding it to Reticulated Python.

From IU, Andre Kuhlenschmidt and Deyaaeldeen Almahallawi are exploring how ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation strategies could help reduce the cost of gradual typing. In particular, they are working on implementing Schml: a compiler from the gradually-typed lambda calculus to C.

In addition to AOT compilation, the folks at IU are exploring tracing JIT compilation as a means to make gradual typing faster. More specifically, Spenser Bauman talked about Pycket, an alternative implementation of Racket that uses RPython/PyPy to dramatically lower the overhead of gradual typing (also see the recording of Spenser’s talk on the topic at RacketCon and his ICFP paper).

Usability

On the usability side, both Shriram Krishnamurthi and Ambrose Bonnaire-Sergeant made observations on what it takes to get gradual typing in the hands of real software developers.

Shriram approached the topic from the angle of CS education, which is the focus of the Pyret language, and shared what the Brown language group is working on. While Pyret doesn’t exactly fit the mold of gradual typing, it’s a close cousin since it’s a dynamically-typed language that explicitly takes design cues from the best parts of statically-typed languages. That approach lets CS beginners think in terms of types (the approach spearheaded by HtDP and Bootstrap) without having to battle a typechecker from the start.

For professional software developers, a major concern with gradual typing is that writing type annotations may be a tedious and time intensive task. Ambrose, who is the creator of Typed Clojure, shared some preliminary work on how to cut down on the tedium by inferring gradual type annotations by instrumenting programs for a dynamic analysis. The hope is to be able to infer both recursive and polymorphic type annotations automatically from tests (you may also be interested in Ambrose’s recent ESOP paper on Typed Clojure).

Implementation Techniques

Finally, several talks focused on alternative implementation techniques for gradual typing that provide a variety of software engineering benefits for implementers.

From Maryland, Brianna Ren gave a talk on Hummingbird, a just-in-time typechecker for Ruby programs (also see the upcoming PLDI paper by Brianna and Jeff Foster). The basic idea is that it’s hard to implement a traditional static typechecker for a language that heavily relies on metaprogramming, in which the fields/methods of classes may be rewritten at run-time. This is particularly tricky for frameworks like Ruby on Rails. Instead of checking types at compile-time, Hummingbird actually executes the typechecker at run-time in order to be able to accurately check programs that use run-time metaprogramming. To reduce overheads, she uses a cache for typechecking that is invalidated when classes are modified.

Stephen Chang gave a very different view on metaprogramming in his talk, which focused on implementing typecheckers using metaprogramming (the trivial Typed Racket library is an offshoot of this work). His key idea is that typecheckers share many aspects with macro-based metaprogramming systems, such as the need to traverse syntax and annotate it with information. Since they share so much in common, why not just implement the typechecker as a macro? Stephen demonstrates that not only is this possible, but that it’s possible to implement a wide variety of type system features this way including (local) type inference. The connection to gradual typing is that even a gradual type system can be implemented as a metaprogram by integrating the generation of dynamic checks into the macro transformation process.

The last talk of the day (but certainly not the least), was by Michael Vitousek, who focused on the transient implementation of gradual typing (first described in his DLS paper). Traditionally, gradual type systems have implemented their dynamic checks using proxy objects that wrap method implementations with both pre- and post-checks. Unfortunately, this implementation technique often conflicts with the underlying language. Since proxying changes the identity of an object it can interfere with object equality tests. Instead, the transient approach bakes the dynamic checks into and throughout the typed code to implement a “defense in depth” against inconsistencies with untyped code. The great thing about this implementation technique is that it doesn’t demand any specialized support from the underlying language runtime and is therefore easy to port to other languages (like JavaScript).

Conclusion

Hopefully this blog post helps provide a better picture of the state of gradual typing research. The exciting thing about gradual typing is that it contains both interesting theoretical problems and also connects to the practical needs of software developers.